What is a Creative?

Making meaning in the machine

I was first addressed as a ‘creative’ in 2018, as a newbie freelance copywriter at a marketing agency. At the time, I wondered why my manager couldn’t just call me a writer. And even though my job included providing creative direction for the graphics accompanying the text, ‘creative’ still felt off.

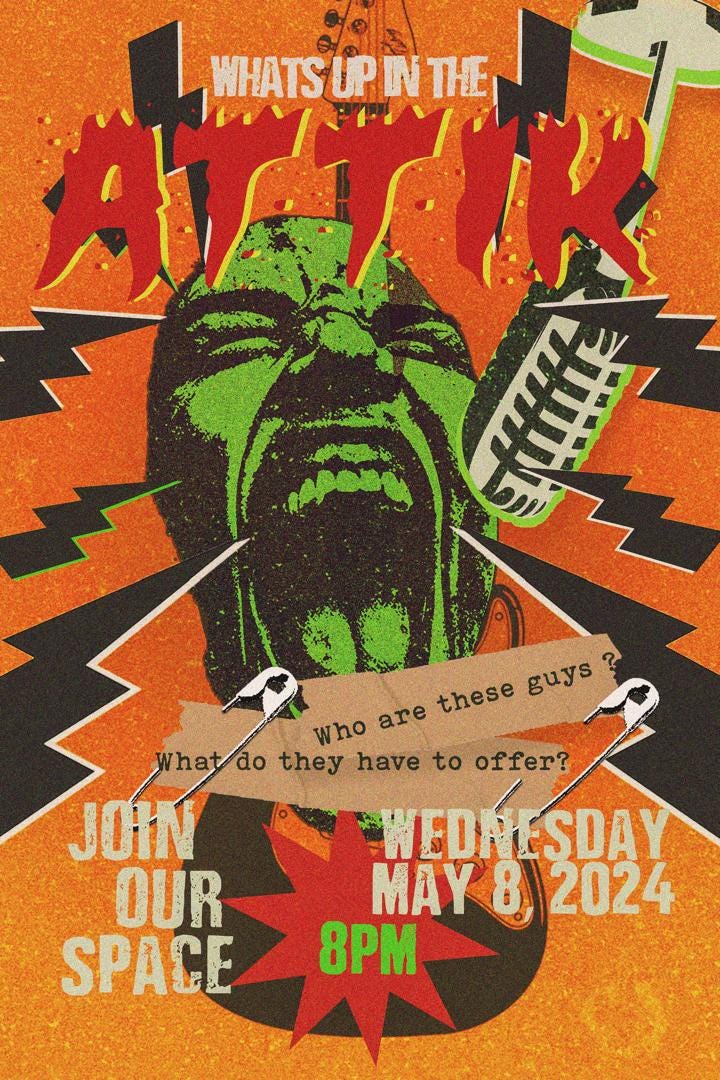

Since then, I have been considering this identity. This year, I put the label on my X bio. Still, when I am asked, “What do you do?” I fumble through the list of things I’m involved in, never using the label that feels just as ambiguous as my work. Because even to me, ‘creative’ carries connotations like this:

This is why I want to answer the titular question.

What is a Creative?

Creative

noun

a person whose job is to suggest new ideas or design, draw, or write things:

The company has a team of 10 creatives working on the project.

Creativity is an inherently human trait, and it is not limited to artistic products and pursuits. We use this ability in science, in solving our day-to-day problems, and in conducting business. Yet for some reason, some people are specifically labelled ‘creative.’

If you are one such person, then you may have seriously considered the word. In my own enquiries, I often dig up its roots in corporate capitalism, so dictionary definitions like the one above did not surprise me. But before I analyze what makes a person a creative and discuss their place within late-stage capitalism, I must bring up a different label, the one I believe every person called a ‘creative’ actually wants to be addressed as.

Artist

An artist is a person who makes art.

According to Francis Edward Sparshott’s The Theory of the Arts:

Art is a diverse range of cultural activity centered around works utilizing creative or imaginative talents, which are expected to evoke a worthwhile experience, generally through an expression of emotional power, conceptual ideas, technical proficiency, or beauty.

Let’s contrast this definition with the concept of ‘content,’ which I find to be to the ‘creative’ as art is to the artist.

Thomas J. Bevan, in his 2021 essay, writes, “Art- in procedure, in intention, in temperament if you like- is the opposite of content. Content is a transaction presented as utilitarian exchange, art is an emanation of the spirit presented as a gift. These are two fundamentally different modes of being and as such lead to two fundamentally different kinds of end product.”

Content is a hollowed-out version of creations that might otherwise have been called art. My brain associates the word with endless, mostly slop, created primarily to addict audiences and please algorithms. Even though creating content requires effort, time, artistic skill, and resources, it feels soulless and disposable. Burdened by a profit-making agenda, its expression of emotional power and beauty is diminished.

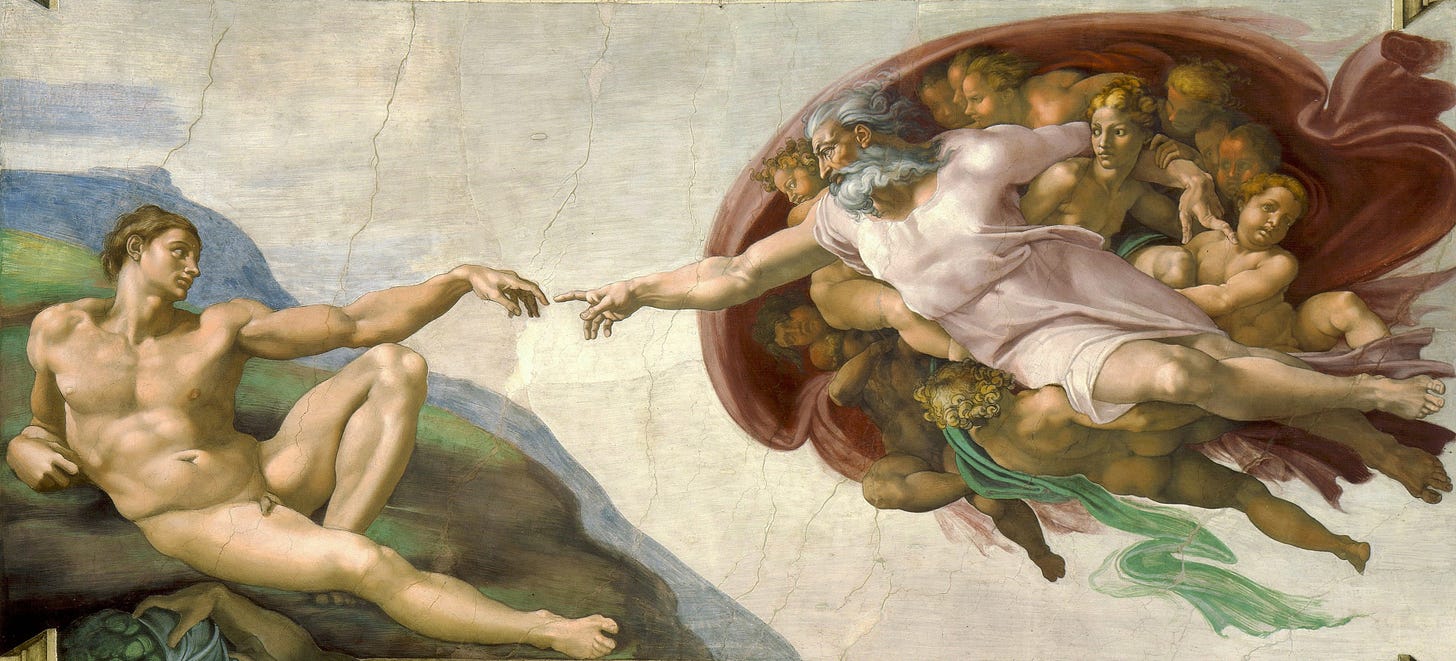

But this dichotomy between art and content is fragile because we can argue that art is also made with the intention of making money. In fact, the conceptualization of artists as people who work for passion rather than to make ends meet is a relatively recent idea. For the last centuries, painters, sculptors, musicians, etc., have been considered elevated craftspeople. Art was a trade people trained for in guilds, culminating in presenting their “masterpiece” and gaining the right to offer their services as master craftspeople.

Over the last two centuries, art began to be practiced as a hobby, and professional artists began creating art based on their own ideas rather than solely on commissions from others. When all works were commissioned, there was no such thing as a non-professional artist. Now, like Bevan, most of us see art as an emanation of the spirit, offered as a gift.

Content and the Death of the Gatekeepers

As overwhelming as the barrage of content we engage with every day might feel. As frustrated as the constant drive to like, share, buy, subscribe, register, and join might leave us, we must appreciate its benefits. Yes, content exists for capitalism, but it is also born of the death of the gatekeepers and the democratisation of the arts.

There is a certain sophistication and superiority that the word ‘art’ connotes, and this is a by-product of its association with the European aristocracy. Bri Janes, in The Internet and the Democratization of Art, discusses this:

“Painting, metal casting, and sculpture became wildly popular amongst aristocrats who commissioned portraits of themselves or religious scenes that inspired them. This is why most of the art you’ll find in museums from around 3000 BC to the 1700s—at least, the art that wasn’t looted in colonial conquest—is of royalty or religious depictions. Perhaps if Johnny Blacksmith could have afforded a piece to stand the test of time, we’d have a sculpture of a beefy bearded guy with a sledgehammer alongside Michelangelo’s David.

As a result, certain art forms began to split along both class and racial lines. Those biting Greek stage plays were derided as crass and low-class by the political subjects they parodied. A wave of religious and ethnic zealotry in both medieval and colonial Europe caused things like pottery, weaving, and beadwork to be viewed as “primitive” due to their popularity in civilizations from the Americas, Asia, and Africa.”

As European feudalism waned and industrialization grew, the middle class emerged with enough disposable income to engage with the finer things of life. They created new art forms, such as printmaking, inking, photography, and film. The average earner could afford these pleasures without commissioning a canvas worth thousands of dollars.

Today, the internet has further democratized the production and consumption of art. We can now share our ideas over miles and access once-gatekept information on how to bring our imaginations to life.

You don’t have to chase publishers around for hundreds of people to read your essay; you have Substack. You don’t need studio executives to accept your screenplay; you have YouTube. But with this liberation from the need for institutional support comes the creator’s direct responsibility for marketing and selling their work.

Content and The Creative

One thing about content that I find even more of a differentiator from art than the money-making agenda is that it must be rapidly produced. While we celebrate our access to art, this newfound abundance has led to a devaluation of our products. To outcompete the millions of others vying for attention, the creative must sacrifice the quality and depth of their creation.

The media through which most creative products are distributed further reduces them to content. There is a significant difference between watching a video on a projector in a dark room with people, followed by a conversation, and watching a video when it pops up on your TikTok for you page. We do not immerse ourselves in a graphic design piece on someone’s Instagram feed as we do a painting exhibited on a gallery wall.

Another differentiator between art and content is that content is very strategic, and many elements included in its composition exist not because of the maker’s stylistic preferences but to hook audiences. And for the creator, the dread of a deadline and the need for shortcuts replace the reflective journey of bringing something worthwhile to life.

An artist

An artist is someone who creates with the intention of expressing something personal, emotional, or philosophical. Their work often serves as a mirror, reflecting their inner experience, social realities, or abstract ideas. The core drive is expression.

The artist asks, “What do I feel, and how can I show it?”

The Creative

A creative

A creative is someone who uses imagination and innovation to solve problems or communicate ideas, often within a context that involves strategy, audience, or function — like marketing, design, branding, or storytelling. The core drive is communication or innovation.

The creative asks, “How can I make this idea work, connect, or inspire action?”

While every artist is creative, not every creative is necessarily an artist.

In the X post from the start of this essay, the author makes a false assertion. They deride the label ‘creative’ for being non-specific, yet consider ‘artist’ a specific one. Michelangelo was a sculptor, painter, architect, and poet. Michael Jackson was more than a musician; he wrote and produced his music videos, choreographed his dance performances, and had so many creative roles we will never fully acknowledge.

For me, the discomfort around the word creative no longer stems from its vagueness or its ties to consumer culture. It comes from the tension between what I do and how I see myself. Even as someone who writes compulsively, who has made a living through words, I hesitate to claim the title writer because of what I believe it should entail: publication, readership, recognition. Perhaps that is the curse of being a creative in this era of endless output and shifting definitions. We are constantly measuring our worth not just by the depth of our work, but by how visible it is.

Still, I’m settling into the label. To see the creative not as a lesser form of the artist, but a reflection of the world we live in—one that asks us to be many things at once. The creative is an artist who adapts. Who moves between expression and survival, between meaning and marketing, between the impulse to make and the demand to perform.

And while we attempt to build a more sustainable system, we continue to create. Because even in a world that commodifies imagination and alienates creators from their creations, outputs will always express the self. In that sense, being a creative is a form of resistance. It’s staying alive to beauty, even as we work within the machine.

Author’s Note:

It’s been a while I published here, but my essay on symbolism as it relates to people from Akwa Ibom state was published by the Anyek Iyak Foundation for Arts and Culture last week.

I chose Ekom’s designs because I think they are beautiful and encapsulate the tension of producing content and making art.

What else can I say? Let’s just do what we can and keep making this world a beautiful place.

Till next time. Like, share, connect with Kuffy Eyo.

Artist’s Bio:

Ekomobong Udoh-Nnah is a graphic designer who specializes in storytelling through deeply researched and culturally nuanced design. His work explores immersive and electronic themes with a focus on resonating authentically with audiences. Influenced by visionaries like Samuel Ross, Hassan Rahim, and Eric Hu, he aims to transcend traditional graphic design boundaries and shape design across multiple industries. His evolving practice embraces design not only as a visual form but as an omnipresent force shaping experiences.

Lovely read🙌🏾

Thank you for the feature ❤️❤️

Wow this is a very beautiful read ❤️

I relate so well with this. Thank you for breaking it down this way ✨